26 Jul 2022

Portfolio Manager Mathew Kaleel and David Elms, Head of Diversified Alternatives, consider the lessons that short squeezes can offer about the inherent danger of carrying excessive leverage or short positions during periods of heightened risk and illiquidity.

Key takeaways:

The announcement by Elliot Investment Management on 6 June 2022 that it is seeking US$456 million in damages[1] from the LME (London Metal Exchange) has brought attention back to the debacle in the nickel market, which saw the market effectively cease trading for two weeks in March[2]. It highlighted a rare but dramatic market dislocation known as a short squeeze. While uncommon, short squeezes manifest over time in different markets, and while the impacts vary, the causes are similar. This article will look at three instances of short squeezes over the last 15 years, all of which we have experienced – in one way or another – as a team, and the lessons we have drawn from each.

Short squeezes have been an impactful feature in financial markets over the last two centuries, often occurring at times of broader market dislocation. One of the better known and early short squeezes involved the speculator Daniel Drew, who was active on Wall Street from 1840 to 1875, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, a stalwart of Wall Street and early investor in railroads (among other business). Drew shorted stock in the New York and Harlem Railroad Company in 1864, hoping to gain from a price fall, however he faced off against motivated, well-funded buyers, who were able to force the price up significantly. Drew was reported to have lost US$500,000 at the time.

A short squeeze is defined as a sudden, dislocated increase in the price of a commodity or security, resulting from an excess of short selling that needs to be unwound.

A number of underlying preconditions are necessary for a short squeeze to occur:

While losing money on both longs and shorts is painful, what makes short positions additionally risky is the fact that – other than in highly unusual situations – losses on longs are limited by the value of a share falling to zero, whereas losses on shorts are unlimited. If a long position underperforms, the problem shrinks, as the price falls and the position reduces in size. On the short side, as the price rises, the position gets larger and the problem also grows, dangerously so if the price rise is big or fast, as it is in a short squeeze. This, along with the technical complications of borrowing securities and managing margin calls, makes short selling a complicated undertaking, far from being just ‘longs with a negative holding’.

Over the past 15 years, the Diversified Alternatives Team has experienced multiple shock events in stock and commodity markets, including three well-documented short squeezes. We will look at each of these and the impact and learnings from these unusual but significant market events.

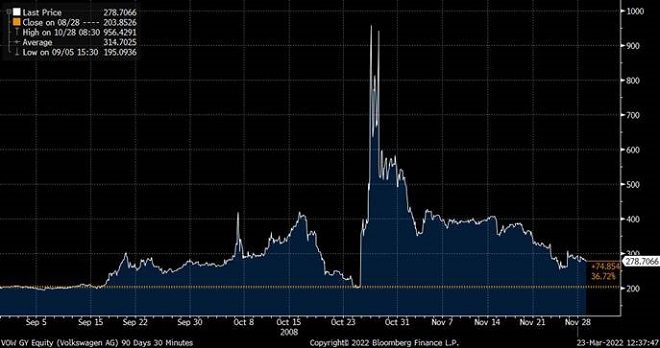

Source: Bloomberg. 1 September 2008 to 1 December 2009 in euros. Past performance does not predict future returns.

The history of German automakers Porsche and Volkswagen had been interlocked for many years, with Porsche owning a minority stake in Volkswagen. From there, Porsche accumulated additional stock in what was then a highly indebted Volkswagen over the course of 2008, with short sellers on the other side assuming that the rise in prices was not sustainable and that Volkswagen stock should trade lower.

At that point it was assumed that the global financial crisis (GFC), playing out at the time, would flow into a collapse in demand for automobiles. The catalyst for the short squeeze and imbalance occurred in October 2008, when Porsche announced on Sunday, October 26, 2008[3] that it had accumulated an economic interest of approximately 74% of the stock in Volkswagen. With a fixed shareholding of 20%, due to the ‘Volkswagen Act’ from the German state of Lower Saxony, this meant there was only a free float of 6% of stock available versus 12% short interest held by short sellers.

The announcement from Porsche resulted in short sellers seeking to buy back stock. However, with an imbalance between the free float (6%) and short interest (12%), there was not enough stock available to close short positions. The ensuing short squeeze saw the price of Volkswagen stock rise by 450%, from around EUR€200 to just over EUR€900 between 24 October and 28 October – for a (very) brief period making Volkswagen the most valuable stock in the world.

Once short sellers had effectively covered their positions, the stock collapsed over the following month, falling back below €300. The chaos caused by this short squeeze saw many hedge funds either closed or severely impacted. It contributed to personal tragedy as well, with German industrialist Adolf Merckle taking his life in early 2009 amid the fallout from the GFC, a year after suffering substantial losses on the short side of Volkswagen.

The Volkswagen short squeeze resulted in considerable controversy, with legal action by impacted short sellers against Porsche ongoing at the time of writing, nearly 14 years after the event. The controversy narrowly centred around whether Porsche’s actions constituted market manipulation. More widely, it raised questions about German market oversight and governance, the attitude of the German regulators to short sellers, and German companies themselves. Failure to learn from the lessons of Volkswagen arguably contributed to the rise and fall – amidst allegations of fraud and embezzlement – of German payments processor Wirecard more than a decade later in our view.

Post-event analysis identified potential improvements to our investment process at both the micro level (managing the risk of short positions in individual names) and at the macro level (ie. how to build a portfolio that was more robust to a highly challenging environment like the GFC, which made the Volkswagen short squeeze possible). Specifically on the micro side, the takeaways related to the quicker identification and response to potential squeezes, as well as management of position sizing, and the mechanics (eg. borrowing stock) of maintaining a short.

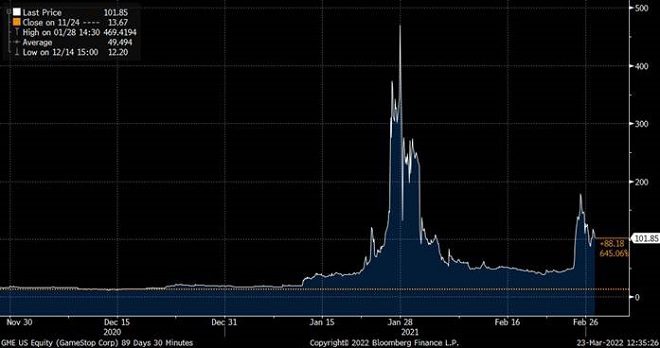

Source: Bloomberg, 3 November 2020 to 26 February 2021, in US dollars. Past performance does not predict future returns. Background

In January 2021, shares in US video game retailer GameStop (market ticker: GME) were hit by a short squeeze, with the stock price rising from approximately US$17 to over US$300 between 5 January and 27 January. Incredibly, the short interest in the stock equated to approximately 140% of the free float, creating a highly unstable situation with obvious risk if short sellers began to cover. While Volkswagen and GameStop shared the perception of being a compelling short on valuation grounds, GameStop had obvious concerns on the viability of its core retail business as the gaming market transitioned to streaming and COVID damaged many bricks-and-mortar retail businesses.

Michael Burry from ‘The Big Short’ film arguably paved the way for the GameStop frenzy when he purchased a stake in 2019, based on a view that the stock was ripe for a shareholder-friendly buyback. At the start of 2021, a campaign of targeted retail buying via the WallStreetBets Reddit forum, additional buying from various hedge fund managers, and short covering, saw the stock price go vertical. Following the short squeeze, short positions held by hedge funds subsequently lost billions of dollars of client capital.

The extent of the move led to intervention by a number of brokerage houses, including Robinhood, which blocked clients from purchasing GameStop (and other relevant stocks), highlighting the risk that Robinhood would not be able to post sufficient collateral with clearing houses, on behalf of its clients, to execute orders. These trading restrictions caused outrage in the Reddit communities that retail buyers had organised around. They prompted accusations that the short side of the trade had used its influence to hobble the ability of buyers to follow through on the short squeeze, and that this was a conspiracy by hedge funds against the interests of small investors.[4]

Trading through this period emphasised the importance of being able to dynamically adjust positioning, reinforcing the benefit of experience and agility, and supporting the argument for running a dedicated strategy that seeks to offset losses in dislocated environments. Later in 2021, as the GameStop situation calmed and become more stable, there was an opportunity for investors to take advantage of still inflated valuations, short selling GameStop as a part of a basket of ‘meme stocks’, benefitting as retail speculation abated and valuations normalised.

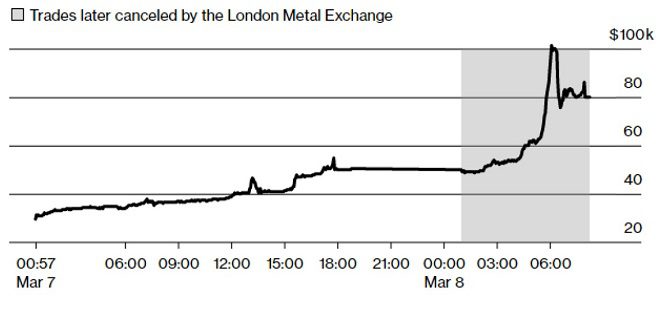

The most recent short squeeze was the nickel market in March 2022[5]. Leading into the event various physical producers, including Tsingshan Holding Group[6], were positioned with significant shorts, either on an uncovered basis or held against production. The catalyst for the short squeeze was the Russian invasion of Ukraine. With Russia a major producer of high-grade nickel, the prospect of supply disruptions saw prices start to climb rapidly, leading to the LME issuing margin calls in the order of US$7 billion, placing several companies and brokers in significant financial distress. The attempt to cover short positions during an invasion by a major nickel producing country saw prices surge from around US$30,000 per tonne to over US$100,000 on 8 March (Exhibit 3), with the number of short positions being covered overwhelming the number of market participants going short.

Source: Bloomberg. Nickel price per (metric) tonne. Past performance does not predict future returns.

While prior short squeezes had clear winners and losers, this short squeeze was fundamentally different. The LME first halted trading on 8 March after significant volatility in the first hour of trading, and then more significantly reversed all trades done prior to the exchange being closed on that date. The net effect was to delete losses for those that were short, and profits for participants that were long – a quite unprecedented intervention.

This is the issue that has caused significant consternation, anger and frustration among those affected, ie. that the exchange deleted executed trades based upon market rules after the event.

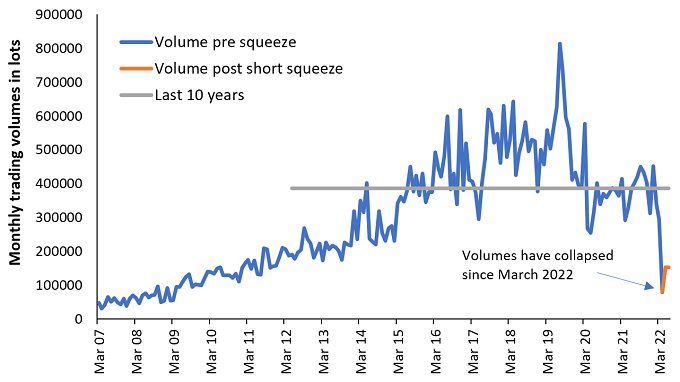

The LME’s actions led to a significant backlash from market participants, including the commencement of legal proceedings reviews by regulators, and the withdrawal of speculators and other market participants. The LME has been penalised in a very direct manner, with a collapse in market volumes and market participation, as Exhibit 4 shows.

Source: Bloomberg, 30 March 2007 to 30 June 2022. Monthly trading volume for LME Nickel; (3 month rolling forward) Past performance does not predict future returns.

Our risk management models were signalling for a reduction in risk and position sizing in nickel going into the short squeeze, due to the significant volatility in markets. The cancellation of trades specifically made to reduce and manage risk, made in accordance with Exchange rules, has raised several significant issues, most importantly that of proper governance – the ‘G’ in ‘ESG’ (Environmental Social and Governance). It is crucial that investors have confidence that a regulated exchange will always act as an impartial counterparty to both buyers and sellers in a market. While the final verdict on the governance of the LME is still to be decided, it highlights the importance of dealing with trusted counterparties that do not act to benefit one side of a market relative to others. Faith that an exchange will operate impartially is crucial to its long-term viability in attracting liquidity and participation.

How the LME deals with the fallout from its decision to cancel legitimate trades and cease trading in nickel for two weeks, without a mechanism for reasonable price discovery during significant geopolitical tension, is a monumental task. One risk for LME is that it opens up an opportunity for a rival to offer an alternative venue for trading. As for other market participants, we seek to transact in the most liquid and well-governed exchanges and markets to reduce and mitigate counterparty risk.

The recent short squeeze in the LME nickel market has reminded us of how fickle markets can be, the inherent danger of carrying excessive leverage or short positions during periods of heightened risk aversion and illiquidity, and the unemotional mechanism in clearing these imbalances.

It also highlighted something much more fundamental. Excess returns are only achieved by taking on some form of risk that other market participants wish to either transfer or mitigate. While an age-old issue, it nonetheless provides further evidence of the importance of appropriate position sizing, diversification, being nimble and having an exit strategy when things do not go to plan. Experiencing a dislocation, such as a short squeeze, is a fact of life if you are running portfolios for long enough. Experiencing losses (Volkswagen), participating in the opportunities short squeezes create (GameStop) and being on the right side of a short squeeze (nickel) all contribute to a pool of experience and knowledge that in our view helps to prepare the team, and better adapt our investment process, for whatever the future holds.

[1] This short squeeze was covered in more detail by Matt Levine (Bloomberg): https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-01-25/the-game-never-stops?sref=3pgYYCsj

[2] A more detailed article on the nickel short squeeze from Jack Farchy, Alfred Cang, and Mark Burton (Bloomberg): https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-14/inside-nickel-s-short-squeeze-how-price-surges-halted-lme-trading

[3] https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinese-tycoons-big-short-nickel-trips-up-tsingshans-miracle-growth-2022-03-13/

[4] Porsche’s press release which led to the short squeeze: https://www.porsche-se.com/en/news/press-releases/details/news/detail/News/porsche-heads-for-domination-agreement-1

[5] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-06/london-metal-exchange-sued-for-456-million-by-elliott#xj4y7vzkg

[6] https://www.reuters.com/business/lme-suspends-nickel-trading-day-after-prices-see-record-run-2022-03-08/

The views presented are as of the date published. They are for information purposes only and should not be used or construed as investment, legal or tax advice or as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector. Nothing in this material shall be deemed to be a direct or indirect provision of investment management services specific to any client requirements. Opinions and examples are meant as an illustration of broader themes, are not an indication of trading intent, are subject to change and may not reflect the views of others in the organization. It is not intended to indicate or imply that any illustration/example mentioned is now or was ever held in any portfolio. No forecasts can be guaranteed and there is no guarantee that the information supplied is complete or timely, nor are there any warranties with regard to the results obtained from its use. Janus Henderson Investors is the source of data unless otherwise indicated, and has reasonable belief to rely on information and data sourced from third parties. Past performance does not predict future returns. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal and fluctuation of value.

Not all products or services are available in all jurisdictions. This material or information contained in it may be restricted by law, may not be reproduced or referred to without express written permission or used in any jurisdiction or circumstance in which its use would be unlawful. Janus Henderson is not responsible for any unlawful distribution of this material to any third parties, in whole or in part. The contents of this material have not been approved or endorsed by any regulatory agency.

Janus Henderson Investors is the name under which investment products and services are provided by the entities identified in the following jurisdictions: (a) Europe by Janus Henderson Investors International Limited (reg no. 3594615), Janus Henderson Investors UK Limited (reg. no. 906355), Janus Henderson Fund Management UK Limited (reg. no. 2678531), Henderson Equity Partners Limited (reg. no.2606646), (each registered in England and Wales at 201 Bishopsgate, London EC2M 3AE and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority) and Henderson Management S.A. (reg no. B22848 at 2 Rue de Bitbourg, L-1273, Luxembourg and regulated by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier).

Outside of the U.S.: For use only by institutional, professional, qualified and sophisticated investors, qualified distributors, wholesale investors and wholesale clients as defined by the applicable jurisdiction. Not for public viewing or distribution. Marketing Communication.

Janus Henderson, Knowledge Shared and Knowledge Labs are trademarks of Janus Henderson Group plc or one of its subsidiaries. © Janus Henderson Group plc.